It’s a regular day at the Noble and Greenough School–assembly doors close at 8:00 a.m. sharp, the library stacks are buzzing with students frantically finishing their group projects, and there might even be a few games of Spikeball and hacky sack going on outside. Except, the Beach is not the grassy patch we have come to know and love. Instead, it’s a real beach, covered in sand with a stunning view of the East China Sea. This is what Nobles could have looked like on Jeju Island, South Korea’s largest island, a place described as a “vacation paradise.”

Frustrated by the number of top-level students leaving South Korea to attend American independent schools, the Korean government established the Jeju Free International City Development Center (JFICDC), which sought to build American-style independent schools on Jeju Island. “They had this idea of this zone with a bunch of independent schools that were clones of American [schools],” Assistant Head of School and Chief Financial and Operations Officer Steve Ginsberg said. In 2010, Nobles was contacted by the JFICDC. Former Head of the Upper School Michael Denning said, “They contacted some of the most highly regarded schools, as measured by rankings, and that’s how they got to us.” While Nobles had received multiple partnership requests each year, some lacking legitimacy, this project seemed like a real possibility. “This email was real and the project got legit publicity. They were reaching out specifically to Mr. Henderson and having conversations. It was sort of like a cold call, but it had enough legs because there was real money behind it,” Ginsberg said.

In 2010, there was a tremendous amount of excitement regarding global education and study-abroad possibilities at Nobles. “Essentially, [JFICDC] was going to pay us a significant amount of money to help establish the school, and they were going to give us a campus,” Denning said. This project presented Nobles with an opportunity for international education. Former Head of School Bob Henderson said, “There was this idea that we would have a healthy exchange back and forth between the two campuses. There’d be Korean kids who came to Nobles and Nobles kids who went to that school.” The proposal’s financial aspect also seemed to appeal to the school. “They offered us a large amount of money; it could have been up to seven figures, and this was after the crash of 2008. But ultimately, it wasn’t about the money for us,” Denning said.

“There was this idea that we would have a healthy exchange back and forth between the two

campuses. There’d be Korean kids who

came to Nobles and Nobles kids

who went to that school.”

This project was considered by the Nobles Board of Trustees and the administration, and broader discussions with students and faculty were limited. “All of the teachers were aware of the plan at the time but I don’t think we were given a lot of details,” Science Faculty Deb Harrison said. Since the project was only in the conceptual stages, it seems that the larger Nobles community did not know much about it. The plan was not kept under strict secrecy: “There was no formal announcement made, but if somebody had asked me at the time if we were having a conversation with a place in Korea, I would have said yes,” Henderson said.

The project never came to fruition, but it seems as though the administration had seriously considered this potential direction for the school. “We got pretty interested. At one point, we were far in planning and were exploring specifics, looking at agreements, etc.,” Henderson said. Although the Nobles faculty never visited Jeju Island, the plan reached a point where a large delegation of Koreans came to Nobles, met with the administration, and toured the school. However, the process came to a halt shortly after that. Ginsberg said, “It was more just information gathering and was an academic exercise.” Despite the end of this possibility, it seems the experience solidified the school’s values; as Denning said, “The further along we went, the more it gave us an opportunity to reflect on who we are, what we do, and what we care about.”

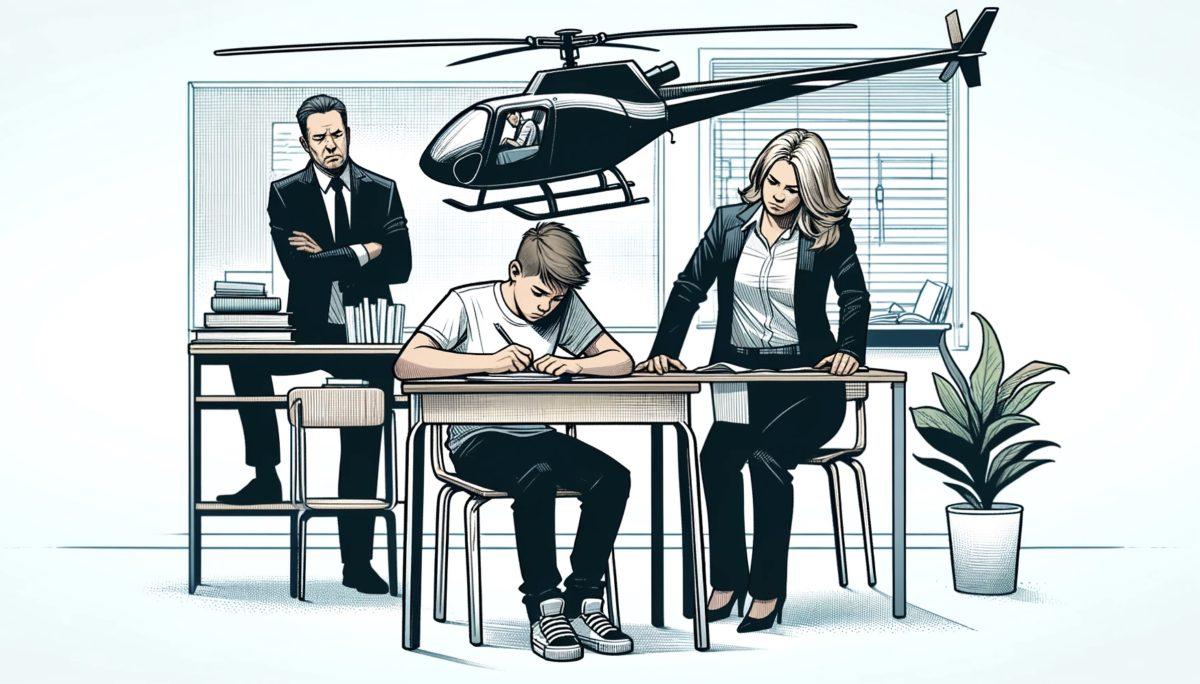

This proposed plan fell through for several reasons (none of which, as The Nobleman’s staff speculated, were because of the threat from North Korean nuclear testing). One key aspect was that the deal would require Nobles teachers to spend time away from the Dedham campus to help launch the new school. “We weren’t willing to risk impacting the experience of Dedham Nobles and the community by setting up another school in Korea,” Ginsberg said. Nobles prides itself on its low student-faculty ratio and the small class sizes, but the budget of this new school called for a much higher ratio—something that the administration was not willing to compromise on. “We weren’t going to be able to actually re-create Nobles within their business model. We were going to have a place that had the Nobles’ name but was going to be a vastly different school. There were certain educational principles that we weren’t willing to compromise on,” Denning said. While this new version of Nobles would be on the other side of the world, school leadership felt strongly that the school’s name was fundamentally rooted in its mission and values. Henderson said, “It started to feel like they really just wanted a brand, and they didn’t really understand the mission.”

“We weren’t willing to risk impacting the experience of Dedham Nobles and the community by setting

up another school in Korea.”

Despite the fact that there is no Nobles Korea, faculty involved in the project reflect on the process of developing the concept as a meaningful experience. “One of the things I’m actually proud of is that we didn’t do it,” Denning said. “It wasn’t a waste of time. We learned a lot about ourselves, what’s important to us, and about the opportunities out there. We grew our network and we got some more experiences as administrators and school leaders.”