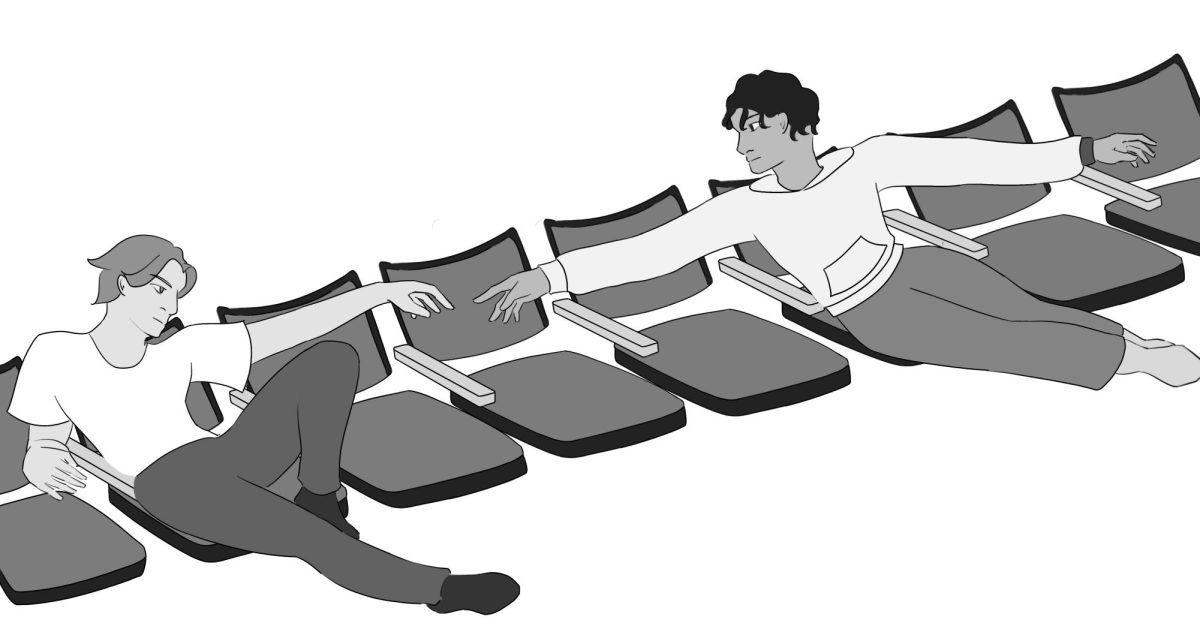

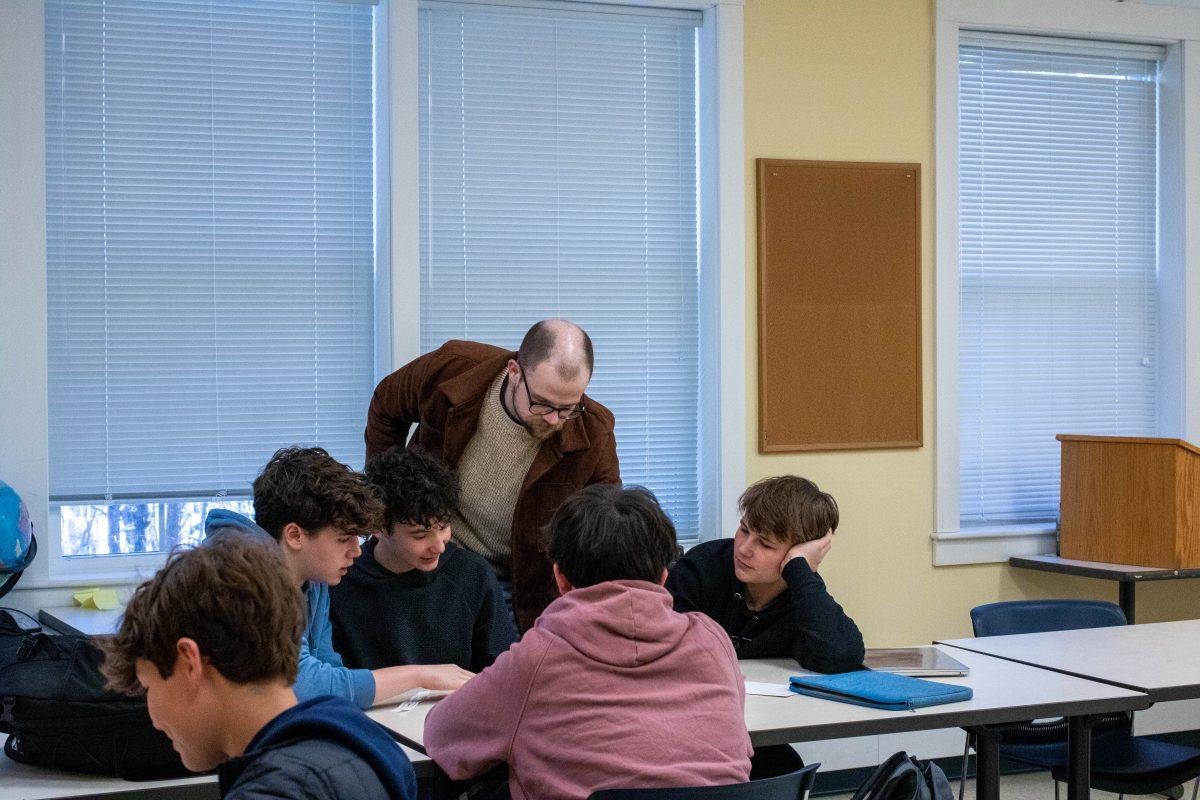

“If we have done our job well as educators, strong supporters of Israel should think that the class is too pro-Palestinian, and strong supporters of Palestine should think the class is too pro-Israel,” History and Social Science Faculty Michael Polebaum said. When teaching the next generation of Americans about one of the most complex conflicts in human history, Nobles faculty aspire, first and foremost, to challenge student preconceptions. “I want you to be more confused and less sure than when you started,” History and Social Science Faculty Steele Sternberg said. Through this methodology, the History and Social Science Department tries not to perpetuate a specific agenda but rather spark discussions to deepen student understanding. “In the world, especially now, it’s really hard for people to listen. Everyone wants to talk. [Nobles] is a space where people encourage you to talk, and they say they’ll listen,” Sanaaya Hora (Class IV) said. With the plethora of resources available to voice student opinions, it is astonishing that many have been so quiet about this conflict on the assembly stage and in classrooms.

“I want you to be more confused and less sure than when you started.”

Some feel that Nobles succumbs to ideological homogeneity in Israel-Palestine discourse. “There’s a way to think at Nobles. If you don’t think like that, you’re not accepted,” Nina Rosa (Class I) said. Due to minimal Arab and Muslim representation on campus, the institution inevitably leans towards a more pro-Israel position. “There isn’t a significant number of students who would naturally hold the views of the Palestinian perspective,” Sternberg said. This uniformity results in a fear of alienation among individuals with differing beliefs. “Students don’t feel like they can say [anything] because they know that other students would talk about it,” Rosa said.

Despite how rampantly homogeneity plagues student dialogue, diversity can be just as damaging. Teaching at the Buckingham Browne & Nichols School (BB&N) during the aftermath of Hamas’s terrorist attack on October 7, 2023, Sternberg observed that the school’s substantial populations of Jewish, Arab, and Muslim community members made students of all perspectives concerned about harming ties with their peers. This resulted in even fewer conversations than Nobles students have. “The student body was much more nervous about talking about this because there were friends to lose, and there were consequences to be had from either side,” Sternberg said. A significant deterrent to student commentary is the fear of offending someone affected by the conflict. “If the other person has experienced something personal in their family that impacts their beliefs on the conflict, you would hurt [them],” Camilla Mangal (Class III) said. This fear is only magnified when the environment is made up of more individuals with connections to Israel and Palestine. Consternation at BB&N was so extreme that Sternberg doubts that even Kehilla’s assembly presentations on antisemitism and Israeli hostages would ever fly there. “No one would sign up to do that kind of presentation because the risk of social blowback would be too great,” he said. When uniformity obstructs dissent and diversity fosters silence, cultivating nuanced dialogue becomes nearly impossible.

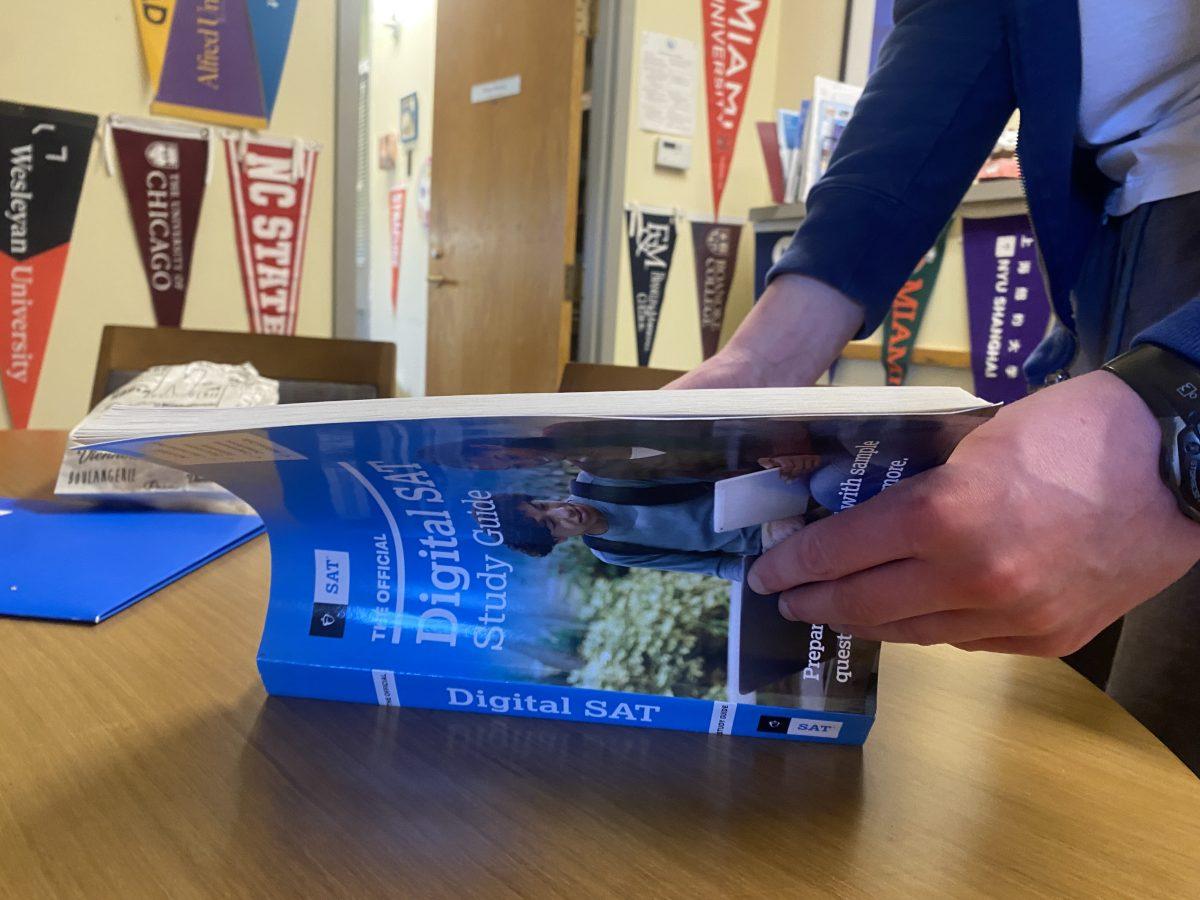

Driving the Israel-Palestine conversation out of the classroom leaves social media as the only mode of engagement, which is conducive to disinformation. Algorithms on these platforms often blind the user to differing outlooks. “It’s easier to talk on social media because most of the people that follow you on social media[…]have the same beliefs [as you],” Mangal said. Instead of interacting with their detractors face to face, users can express more extremist ideas to a loyal audience without much opposition. To combat this dynamic, the History and Social Science Department expanded the Global History I (GH1) curriculum to cover more of the conflict following the October 7 massacre. “It’s okay to be unsure, but it’s not okay to be uninformed,” Polebaum said. Acting on this belief, Polebaum dedicates class time to tackling various misconceptions. “We spend a day talking about what Zionism is, and in that process, we’re talking also about what Zionism is not,” he said. Even with the measures taken to mitigate the spread of misinformation, teens cannot resist the allure of a digital infographic. “Social media is really good at diluting stuff down into [something that is] clickable [or] swipeable,” Polebaum said. While this dilution can make social media a useful tool, it blemishes any opportunity for nuance. “You can quickly just share to your story, and it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, look at X, Y or Z’[…]you’re not actually thinking, right?” Polebaum said. By sharing third-party posts to their stories, users can back up false claims with prominent accounts that have perceived credibility. “You could say ‘No, this person said it. I didn’t make it up. It’s actually true. It has legitimacy behind it. I know what I’m talking about,’” Gabi Burack (Class III) said.

“It’s okay to be unsure, but it’s not okay to be uninformed.”

Social media’s unwavering dominion highlights an essential facet of the Nobles Israel-Palestine conversation: Our history teachers can’t guide us through it. In an institution so academically rigorous, it’s absurd to expect faculty to pause the curriculum to cover the newest developments in a continuously evolving global crisis. “I feel this incredible pressure to get through the content. We could talk about the present, but then my whole schedule and plan gets messed up,” Sternberg said. Not even the extended Israel-Palestine unit in GH1 can ensure holistic schoolwide dialogue. “It was only two weeks, and you could spend a whole lifetime studying it,” Burack said.

Because educators can’t both stimulate and regulate the Israel-Palestine conversation at Nobles, it is the responsibility of students to lead the charge of holding discussions at school and off the web. Some students worry that expressing their opinions will get them into trouble, but teachers claim that they are being overly cautious. “I think students’ perception of what trouble is is misguided and overblown,” Polebaum said. While Nobles’ culture is apprehensive towards confrontation, some schools around the world have encouraged arguments. Studying in Denmark last year, Mangal saw how embracing disagreement establishes a better understanding of important causes. “I think it was less of an issue because the classrooms there supported arguments,” she said. It may feel comfortable to avoid conflict throughout high school, but the quiet alternative is infinitely more treacherous. Students are faced with a choice: either interact with their peers in a meaningful way or just hope the Instagram algorithm doesn’t sway them in the wrong direction.

“I think students’ perception of what trouble is is misguided and overblown.”