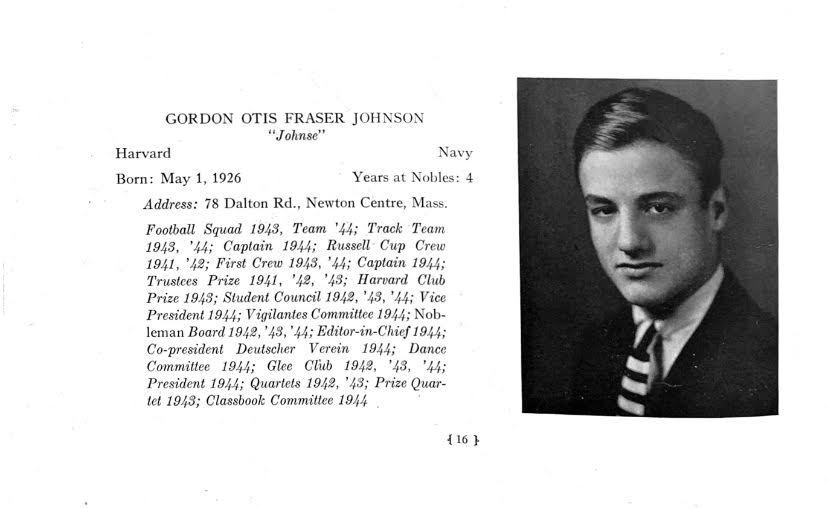

It’s hard to imagine what Nobles will look like 80 years from now. It seems like every year a new development comes up to revamp part of campus or reconsider the very core values we live by. Will the Putnam Library be considered a relic of a bygone generation? What will this school stand for in 2105? To understand how to grapple with these questions, look to Gordon Johnson (N’ 44), the oldest living Nobleman writer, and the second-oldest living Nobles graduate.

At 98 years old, Johnson has learned that one’s purpose is inextricably linked to their community. “The whole purpose of life is to move from being a completely self-centered individual when you come into this world, to learning to be together,” Johnson said. Despite the enormous changes to Nobles since his high school years, he affirms that the value of togetherness has remained constant. “I think Nobles is doing a wonderful, remarkable job bringing people together in modern ways that are way beyond anything that I experienced,” Johnson said.

“The whole purpose of life is to move from being a completely self-centered individual when you

come into this world, to learning to be together.”

Johnson ascribes his longevity to his active lifestyle, kickstarted by Nobles athletics. “I […]feel that I got to be 98 because I got launched into being active at Nobles. I mean everybody did sports!” Johnson said. When he attended Nobles, all students were required to play on Eliot T. Putnam’s football squad. In addition to serving as the team’s quarterback in the fall, Johnson was captain of the track team in the winter and the bow seat of the crew team’s first boat. The track team ran on a wooden track built on top of the football field throughout the winter months and the crew team still rowed on Nobles’ stretch of the Charles.

Nobles was a very different place during World War II when Johnson attended. “The school actually did consider closing up towards the end of the war. Things were that difficult financially [with] getting enough students that could come,” Johnson said. During his senior year, two of his classmates enlisted in the military, shrinking the already meager class of 15 down to 13 graduates by June. These absences, in addition to the enlistment of multiple teachers, caused shifts in the community in order to fill sudden vacancies. “I was only captain of [the crew team] because Bram Arnold had left,” Johnson said.

In addition to community departures, wartime gasoline restrictions changed many students’ commutes to school. During his sophomore year, Gordon Johnson regularly traversed Route 128 by bike to get to campus.

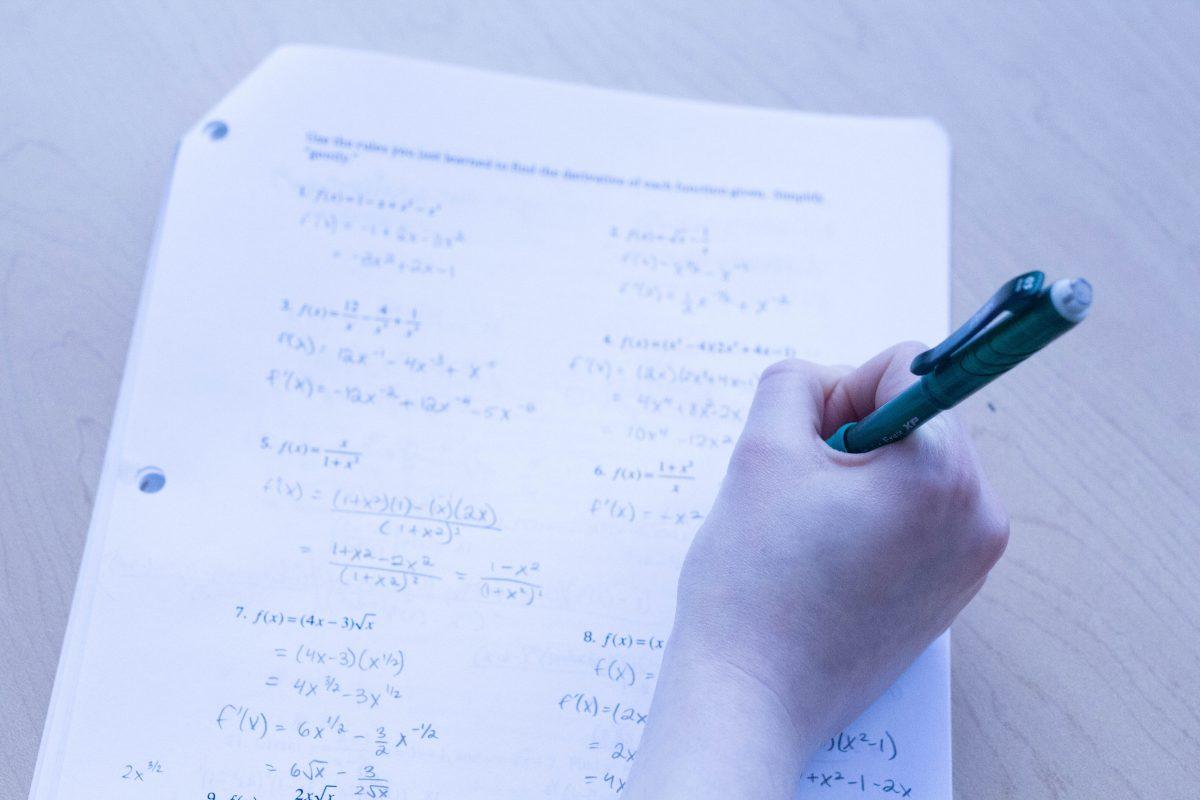

The war also impacted the college application process of the time. Generally, a Nobles graduate’s acceptance to Harvard was effectively given. “You filled out an application and sent it in and I don’t know that anybody from Nobles was ever rejected [from Harvard],” he said. Conversely, during wartime, all graduates had to attend some form of officer training before going to a college selected by their training program. After one year with a Navy officer training program, he was off to MIT despite only taking one science class in all of high school.

Johnson is quite intrigued by Nobles’s current mission statement. He applauds the inclusion of discovery. “Innovation is what’s made this country what it is. Innovation comes from discovery,” he said. It’s the “doing good” part that he’s more skeptical of, as “doing good” is too broad an objective in his eyes. During his Nobles years, Charles Wiggins’s “definition of a gentleman” served as the school’s mission statement. “I hope that if anything comes out of this interview, it will be my thought that Mr. Wiggins’s definition of a gentleman still applies today,” Johnson said. The definition is as follows:

“You filled out an application and sent it in and I

don’t know that anybody from Nobles

was ever rejected [from Harvard].”

A gentleman is a man who is clean inside and outside; who never looks up to the rich for his riches or down on the poor man because of his poverty; who can lose without whimpering; who can win without bragging; who is considerate to all women, children and old people – or those who are weak or serve or who are less fortunate than he is. A man who is too brave to lie; too generous to cheat; whose pride will not let him loaf and who insists on doing his share of work in any capacity; a man who thinks of his neighbor before he thinks of himself and asks only to share equally with all men the blessings which God has showered on us.

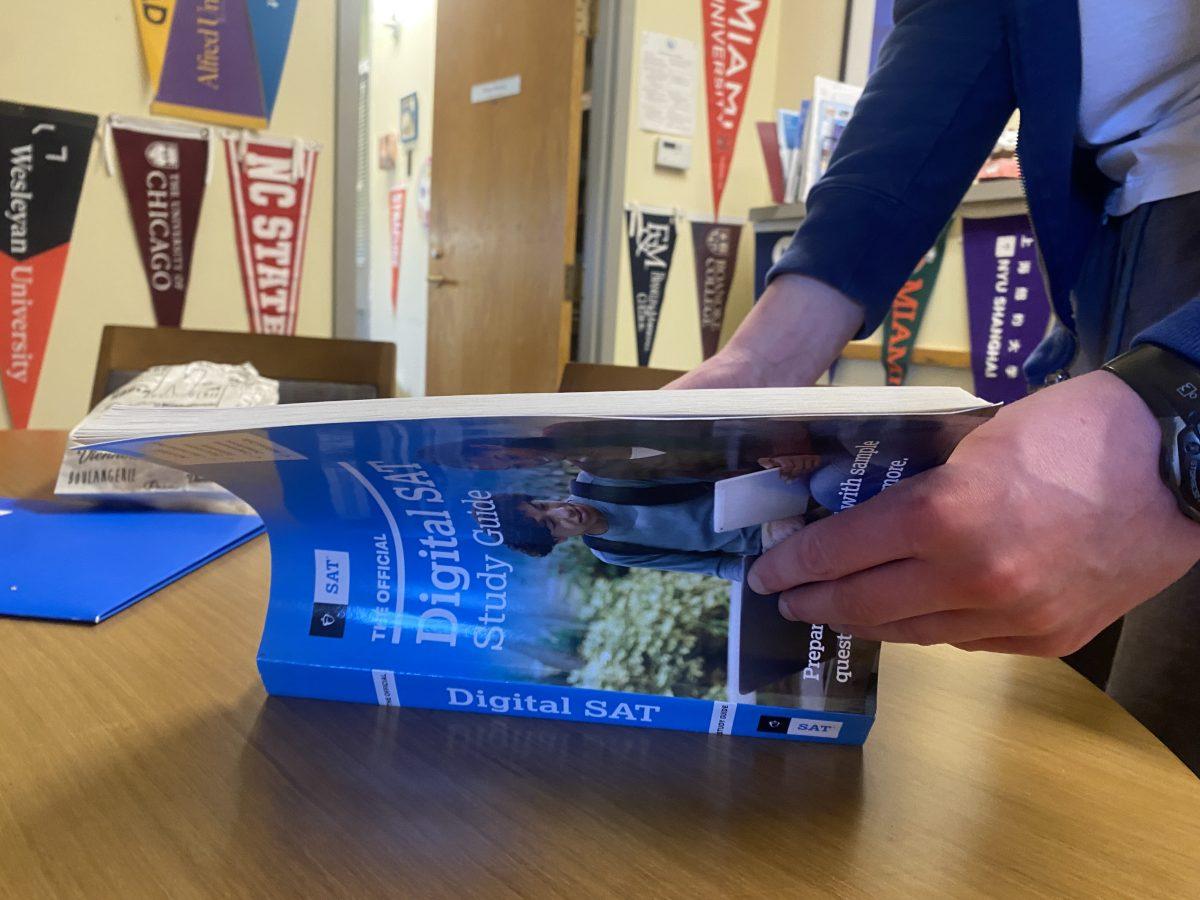

Providing Johnson with the most recent edition of The Nobleman, the former editor-in-chief had much to say about the current state of the publication. “The things you’re dealing with today in the school are incredible. We didn’t get into all those kinds of discussions. We didn’t have EXCEL. We didn’t have Achieve. We didn’t have the ‘long assembly.’ We didn’t have to worry about Zyn on campus. I don’t recall anything about culture or all that kind of stuff. We were just very, very basic.” As an editor, Johnson usually published around four 10-15 page editions every year, which were largely comprised of creative writing pieces. The publication used to generate revenue through running advertisements from local businesses, as well as charging students $3 (just over $53 in today’s money) for a yearly subscription.

Johnson claims that The Nobleman faced little censorship or adult supervision at the time, with the exception of one incident in 1943. Francois Leydet, a Nobles student who had come to the United States with his brother to escape Nazi-occupied France, wrote an article critical of the Russian government. “I have a memory of Mr. Wiggins going up and down the study hall and tearing out a page of Francois Leydet’s 1943 article warning us to beware of Russia because he felt that it was unpatriotic.” The head of school removed Francois’s article from nearly every copy, making the piece one of the only Nobleman articles truly lost to time.

“The thing to do is decide what you really like to do and find somebody who will pay you to do it.”

Before bidding farewell to Mr. Johnson, I asked if he had any advice for the current graduating class. He answered quite simply: “The thing to do is decide what you really like to do and find somebody who will pay you to do it.” Gordon Johnson’s Nobles was not the multifaceted community that it is today. “It was a very basic reading-writing-arithmetic education and in my case, I managed to avoid Chemistry,” he said. Although his Nobles lacked music ensembles, AP classes, and even female students, our shared value of community remains: “Togetherness is the ultimate purpose in life. It’s what God had in mind when he created us.”