On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court ruled to outlaw race-based Affirmative Action in college admissions. This decision means that colleges can no longer consider race as a factor when evaluating applicants.

Importantly, according to the Supreme Court Case “Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College,” “the decision does not prohibit universities “from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” In other words, universities cannot make assumptions about a student’s life, character, or ability on the basis of their racial identity—any impact race might have had on an applicant must be explicitly articulated on an individual basis.

Given the substantial discretion still afforded to colleges, the 2023 ruling has had a mixed impact on racial demographics. Many schools like MIT, Stanford, and Harvard have reported a drastic decrease in racial diversity for the Class of 2028, while others like Williams and Yale saw less of an effect. Differences in legacy and donor preference, sports recruiting policies, essay questions, and financial aid programs all play a role in how much a certain college might have been affected by the decision.

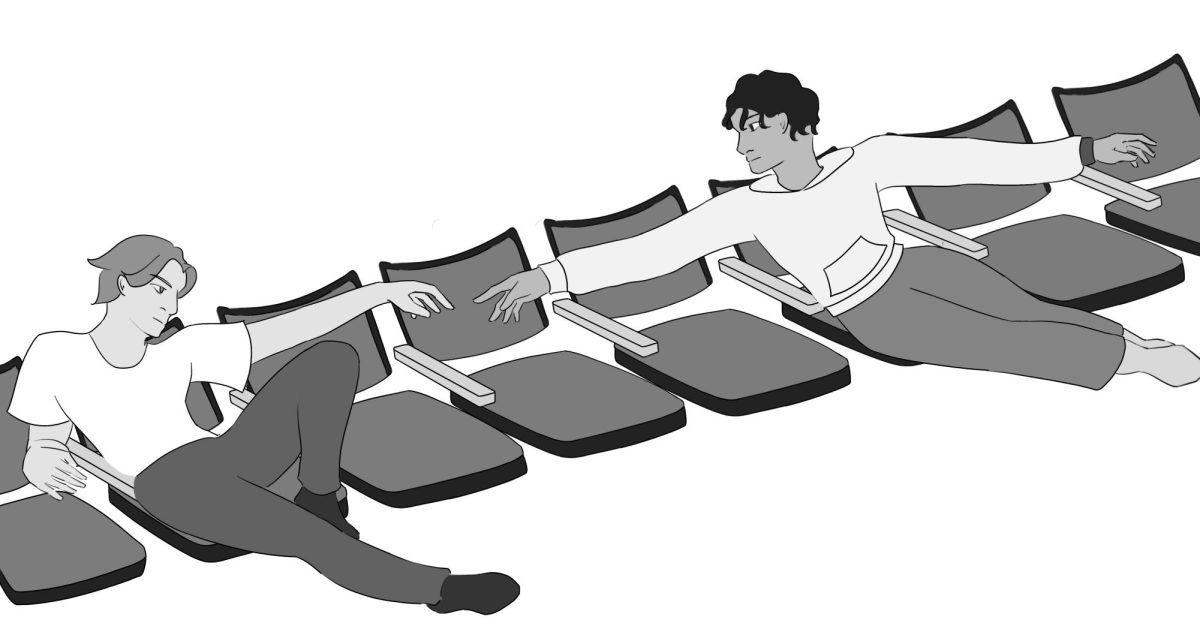

The Nobles community has varied opinions about the Affirmative Action ban. Many who are skeptical about the decision emphasize the importance of diversity in creating a stimulating learning environment. “Diversity is important because it allows students to engage with people from different backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences. I think this helps prepare us for the real world, where you have to collaborate with different groups of people,” an anonymous student in Class I said.

A diverse school community also means that students from underrepresented backgrounds might feel more included and supported. “Being surrounded by people from completely different demographics or backgrounds can be unnerving. People often cluster around people who are like them—whether that be in terms of race, ethnicity, perspective, or shared experience,” Serhan Marvi (Class II) said.

One benefit of race-based Affirmative Action is that it provides assurance to applicants that many of their college peers will have similar experiences to them. Without this assurance, students from underrepresented backgrounds might feel less comfortable applying to predominantly white institutions (PWIs). According to The Hilltop, many Black and Hispanic students in the ‘23-’24 application cycle chose Howard University (a historically black college) over prestigious PWIs due to concerns about finding belonging at a PWI that can no longer practice Affirmative Action.

The Nobles community, regardless of their stance on Affirmative Action, also believes that college admissions should be meritocratic.

Many students who oppose the ban contend that race-based Affirmative Action was a means by which colleges could level the playing field. “A large part of Affirmative Action was to create a basis where everyone had an opportunity and a chance. These measures were necessary, especially when considering the US’ history of systemic racial discrimination,” Camilla Mangal (Class III) said.

Other students believe that race might not directly correlate with a student’s opportunities. In this way, race-based Affirmative Action may have had good intentions but ultimately made college admissions less meritocratic. “The Affirmative Action ban is somewhat affirming for me in the sense that I know that when I’m accepted by a college, it’s not because of my race—it’s because of my own merit,” Nathanael Jean-Gilles (Class II) said.

“The Affirmative Action ban is somewhat affirming for me in the sense that I know that when I’m accepted by a college, it’s not because of my race—

it’s because of my own merit.”

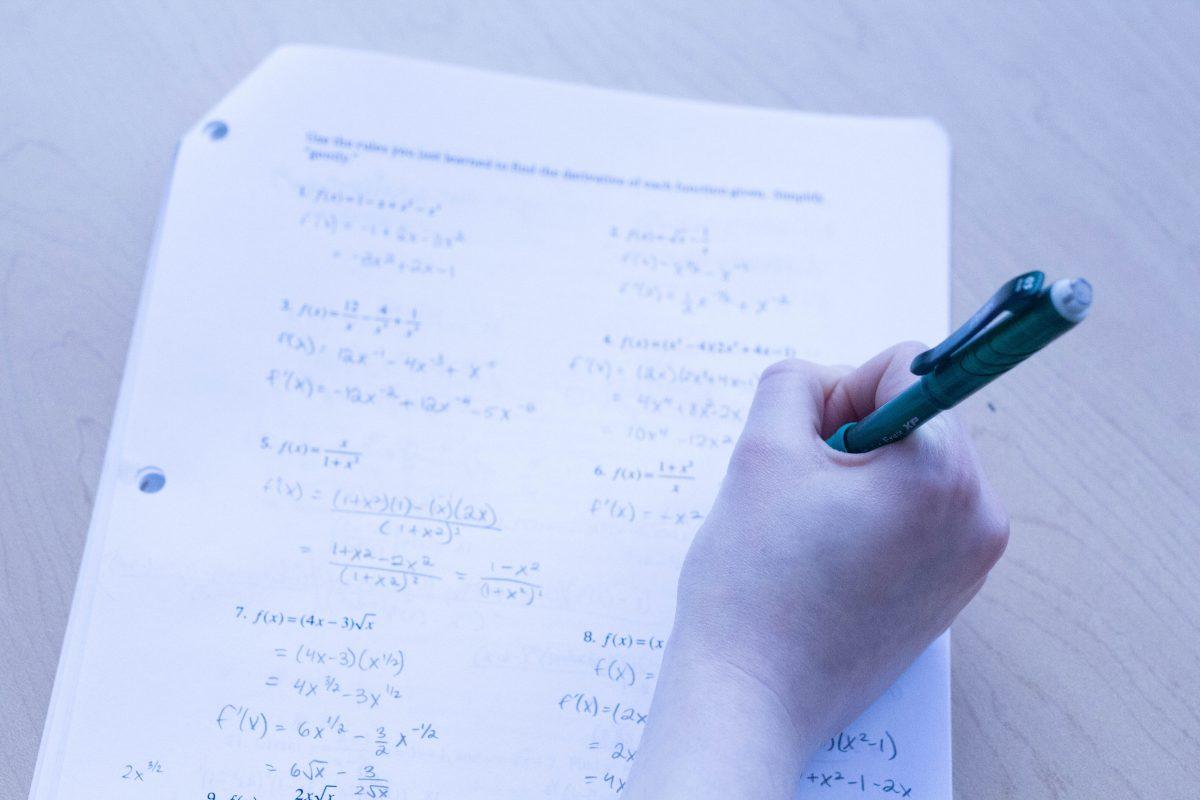

The Nobles community is also concerned about how the Supreme Court decision might impact the college application process. “Many kids have probably felt lots of major and minor ways in which their racial identity, or religious identity, or gender identity, or sexual orientation has potentially been a barrier or an obstacle. This decision puts the burden on them and sort of says, ‘Prove it. Prove that your identity has had some effect on you that should matter in the admissions process,’” General Counsel Beth Reilly said. It is undeniable that one’s racial identity can present obstacles, but these obstacles are often subtle and hard to articulate. Following the Supreme Court decision, if a student is unable to articulate exactly how their racial identity has impacted them, this impact can no longer be considered as part of their application.

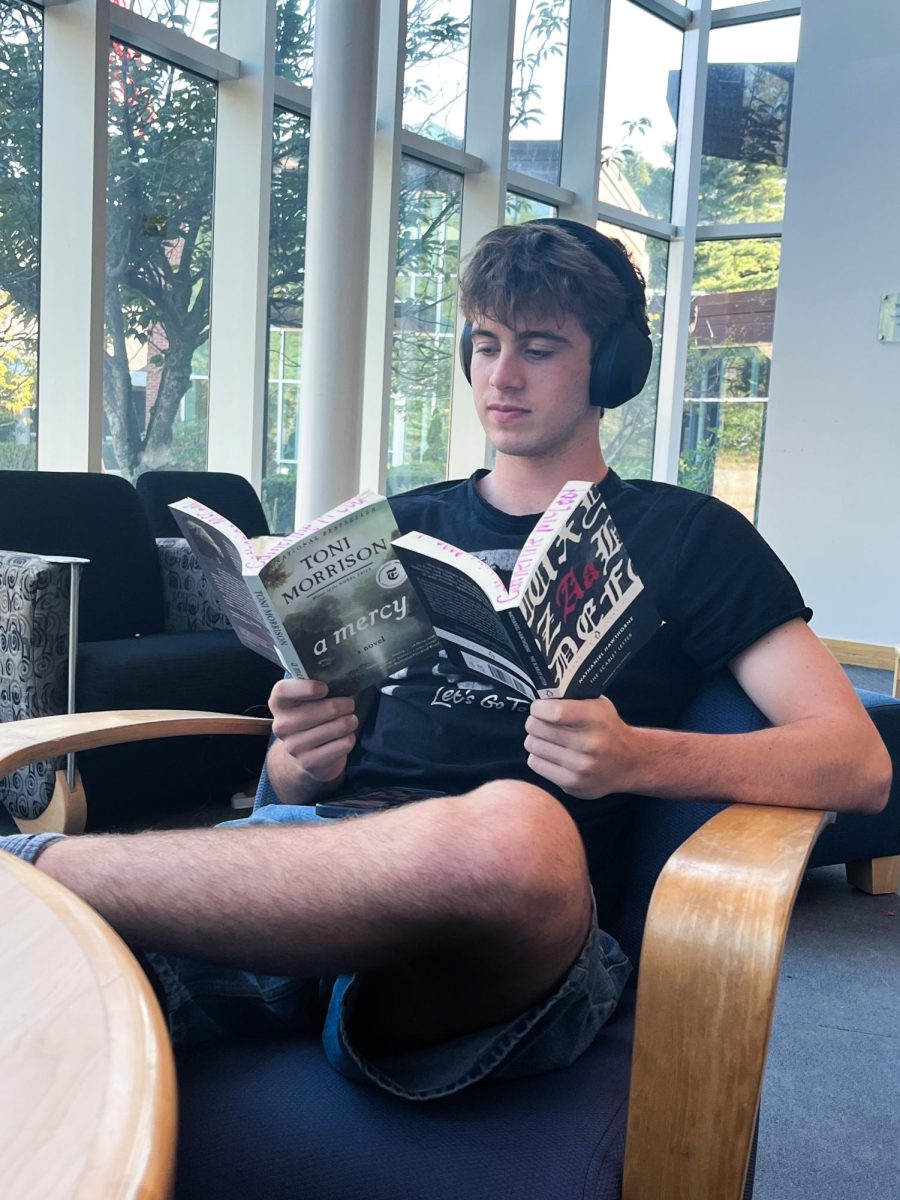

Having to verbalize the challenges one has faced can also be incredibly degrading. “When I write and apply for colleges, I don’t want to sell my sorrow. I feel that it’s very disheartening to have to write or talk about something that has held you back and have that be the reason you get into college,” Christian Gonzalez-Pena (Class II) said.

With these various considerations in mind, how can colleges adapt their admissions policies to continue to promote racial diversity?

“For admission programs within these schools, the question becomes: what questions are you asking applicants, and is racial diversity important to you? If racial diversity is important, then your application may look different than it did the year before in terms of the questions you’re asking,” Co-Associate Dean of Diversity Edgar De Leon said. In light of the decision, it is incredibly important that colleges facilitate ways for students to talk about race in their application. Many colleges have already reconsidered and will continue to reconsider what questions they are asking applicants.

“One of the proxies that a lot of colleges are trying to use is first-gen status, and I think you did see an uptick in first-gen admissions in the last year,” Director of College Counseling Kate Ramsdell said. Compared to Americans in other racial demographics, far fewer underrepresented minorities have received post-high school education. Thus, colleges could potentially use criteria such as “first-gen status” (being the first in your family to receive higher education) to indirectly promote racial diversity. Such practices are considered by the Court to be race-blind and remain permissible under the 2023 ruling.

Though the Affirmative Action ban might be disconcerting, students can take comfort in knowing that colleges still have numerous tools to promote a diverse student body. As demonstrated by the demographics at schools like Yale and Williams, this decision does not mean the end of diversity in colleges–it simply entails a shift in how diversity will be achieved.