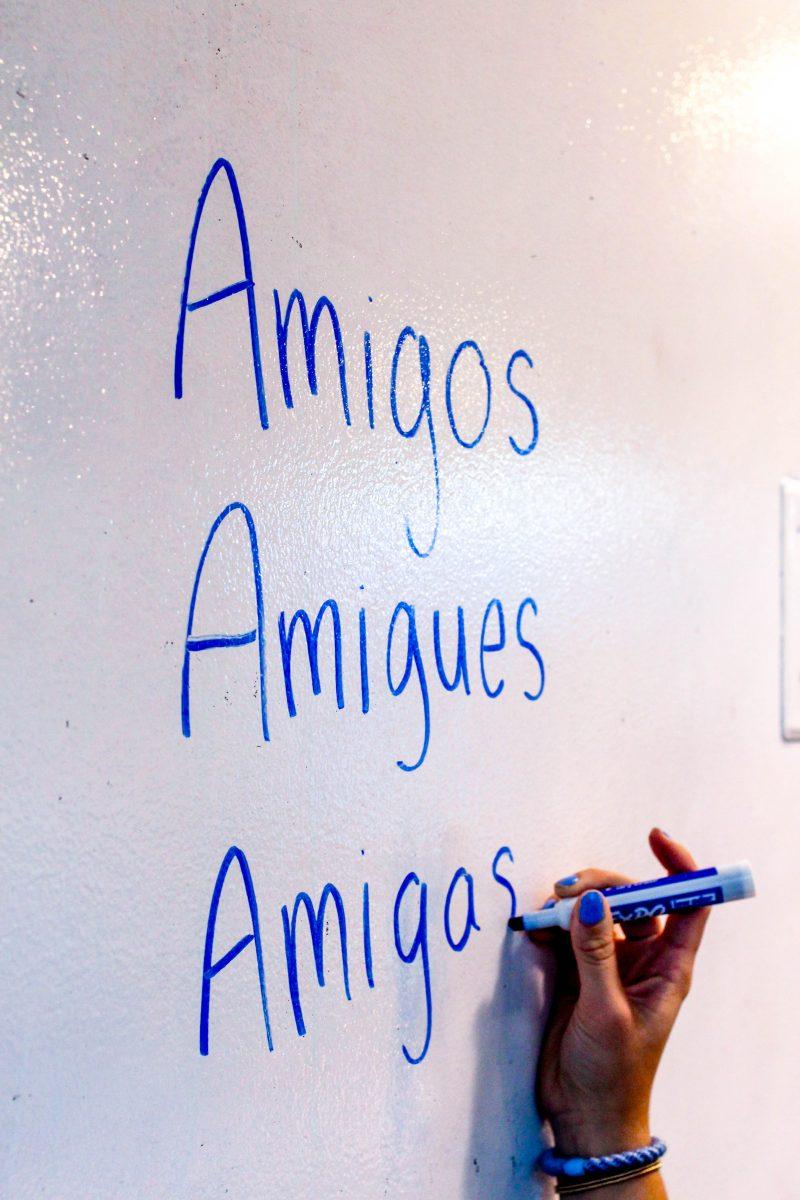

When, across the United States, Latin America and Spain, chicas becomes chiques, amigos becomes amigues, and todos becomes todes, a linguistic phenomenon takes place, and a heated debate ensues. In the Spanish-speaking world, the inclusion of gender-neutral verbiage is contested, and yet at Nobles, we teach gender-neutrality in a portion of our Spanish classrooms. Whether or not Spanish should incorporate gender-neutral endings domestically or abroad boils down to the following questions:

- Should teachers adopt a neutral language when the majority of native speakers do not?

- Does adapting Spanish with more inclusive language actually result in more inclusivity?

- Should Spanish become more gender-neutral?

Firstly, it’s important to understand what modern movements for gender-neutral language in Spanish consist of. The change appears either predominantly in the replacement of the suffix (-es) to previously grammatically masculine (-os) or feminine (-as) nouns referring to people, or the addition of (-X) or (-@-) in its stead, like LatinX or bienvenid@s. Linguistically, the presence of epicenity and ambiguous language implies gender neutrality or ambiguity within a “grammatically-gendered” language; for much of the native population in Latin America and Spain, it’s mostly for this reason that movements for the change to -es have been a difficult transition. Van Otterloo quote, process. However, the usage of -es is more directly inclusive; an implication of neutrality, especially for non-native speakers, is more difficult to comprehend. Ms BA quote, people aren’t just binary. The Real Academia Española, charged with monitoring the Spanish language, labels gender-neutral proposals “artificial and unnecessary” due to the existing inclusion of neutrality in the language’s binary. Argentina, in 2022, banned gender-neutral conjugations in its education systems for reasons of “violating the rules of Spanish and rendering more difficult the learning of Spanish for its youth. ”

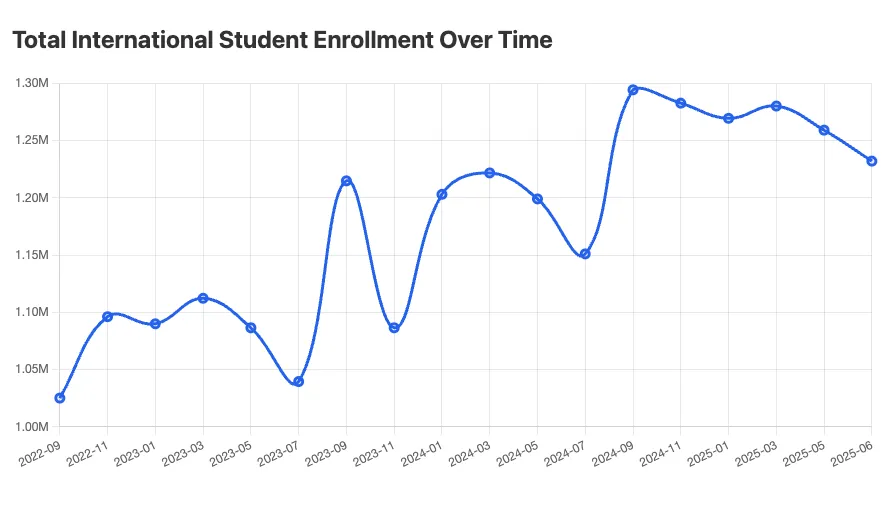

Language is an inevitable product of society, and should be put in the context of the groups that speak it – both native and nonnative – in order to be fully understood. At the moment, gender-inclusive language is mostly used by the vast minority in universities and among the youth populations in the Spanish-speaking world. In the United States, about 25% of native speakers have heard of the term LatinX, though only about 3% use it. However, the percentage has risen from past years, and promotion of gender-neutral adaptations in native communities does exist. Gaby Guzman quote, grandparents. The teaching of gender-neutral Spanish in American classrooms has risen in the past decade, with the interviewed Nobles faculty having heard it around or before the pandemic. In learning a language, Lucas Ilzarbe, goal of learning a language. About 1.2 million people in the United States identify as non-binary, and though the English language has only considered its nouns non-gender-affiliated since the 20th century, a parallel is naturally sought in binary languages to offer the same inclusion., Quote on Spanish speaking not being IT w culture. Within the States, gender-neutral Spanish trends with the rising consideration for gender outside of a binary; outside of the States, the majority culture doesn’t necessarily align with this movement, and neither does the language.

“The reality is that the inclusivity of language

is subjective, and is therefore in the hands

of the different communities that use it.”

The reality is that the inclusivity of language is subjective, and is therefore in the hands of the different communities that use it. However, linguistically, Spanish does encompass gender neutrality. Spanish’s binary trickles from Latin, and in its evolution the language accepted the gender-neutral Latin case by usurping it into the masculine gender, and “the 3-gender system of Latin, with its categorization of all nouns as either masculine, feminine, or neuter, is in fact preserved intact in Spanish”. Mr. Berdugo quote on disservice. Additionally, Spanish grammar contains a linguistic feature called epicenity, in which a word may contain a grammatical gender (like la persona, or the person, which is “structurally” feminine), but actually refers to any sex. El estudiante could refer to a female or non-binary student. This is different from ambiguous gender, in which the article or grammatical gender can be changed without affecting the word’s meaning; a popular example is el mar, or the sea, which can also be written, though more poetically, as “la mar”. One is an umbrella, the other a chameleon.