Clare Struzziery, Staff Writer

February 9, 2024

Talk of cancel culture and polarization has been increasingly present on the assembly stage and in classrooms. However, Nobles is not usually riven with political conflict. Is this because students are cautious about sharing their beliefs?

The Nobleman sent out a survey to a randomized list of 40 students from each class in the Upper School. Ultimately, 124 out of the 160 students responded. The responses were kept completely confidential and were not viewed by any member of The Nobleman staff. Of this sample, 42.7% of students agreed that, at times, they feel or have felt intimidated sharing in class. 14.5% of students strongly agreed. On the other end, 19.4% disagreed and 5.6% strongly disagreed. 17.7% of the population surveyed said that they neither agreed nor disagreed. The results of this question have a 7.61% margin of error. Margins of error are calculated using a 95% Wald confidence interval with a finite population correction factor.

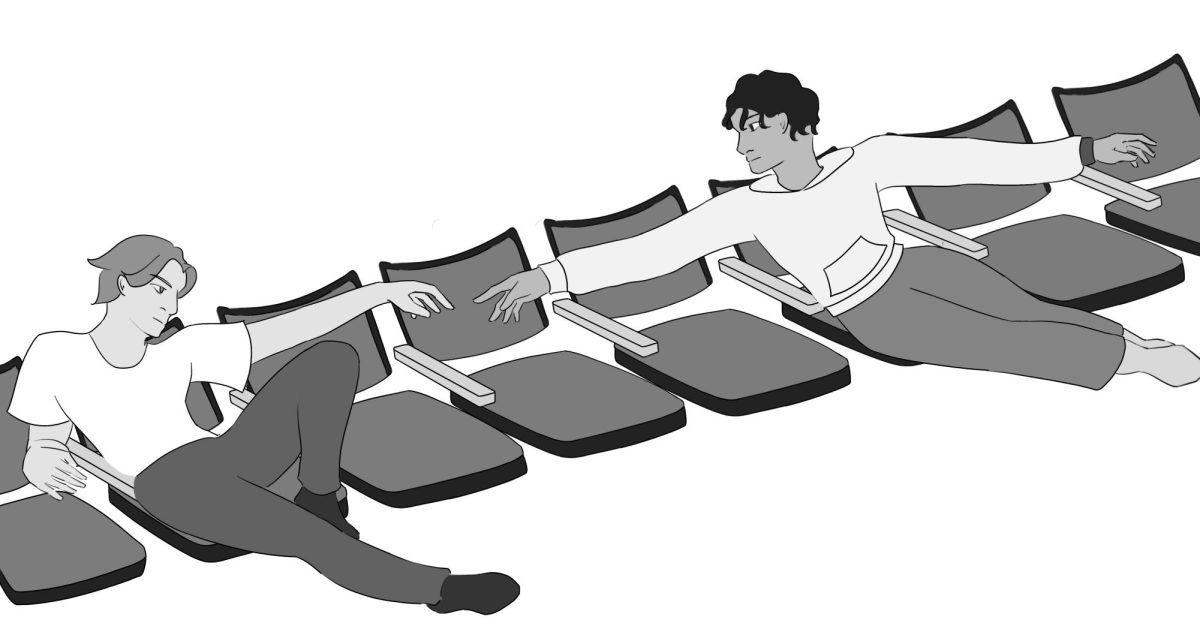

Inside and outside of the classroom, Nobles students seem to avoid controversy. If and how students express their political beliefs is something that they give significant thought to. “The fact that I have to mince my words despite not feeling as though anything I say is offensive, just speaks to the extent to which people feel restricted in their speech at Nobles,” Colin Levine (Class I) said. Steering clear of difficult topics altogether is an approach a lot of students adopt. “When there are conflicts, we tend to just avoid it because we don’t want to be controversial,” Phiona Nabagereka (Class II) said.

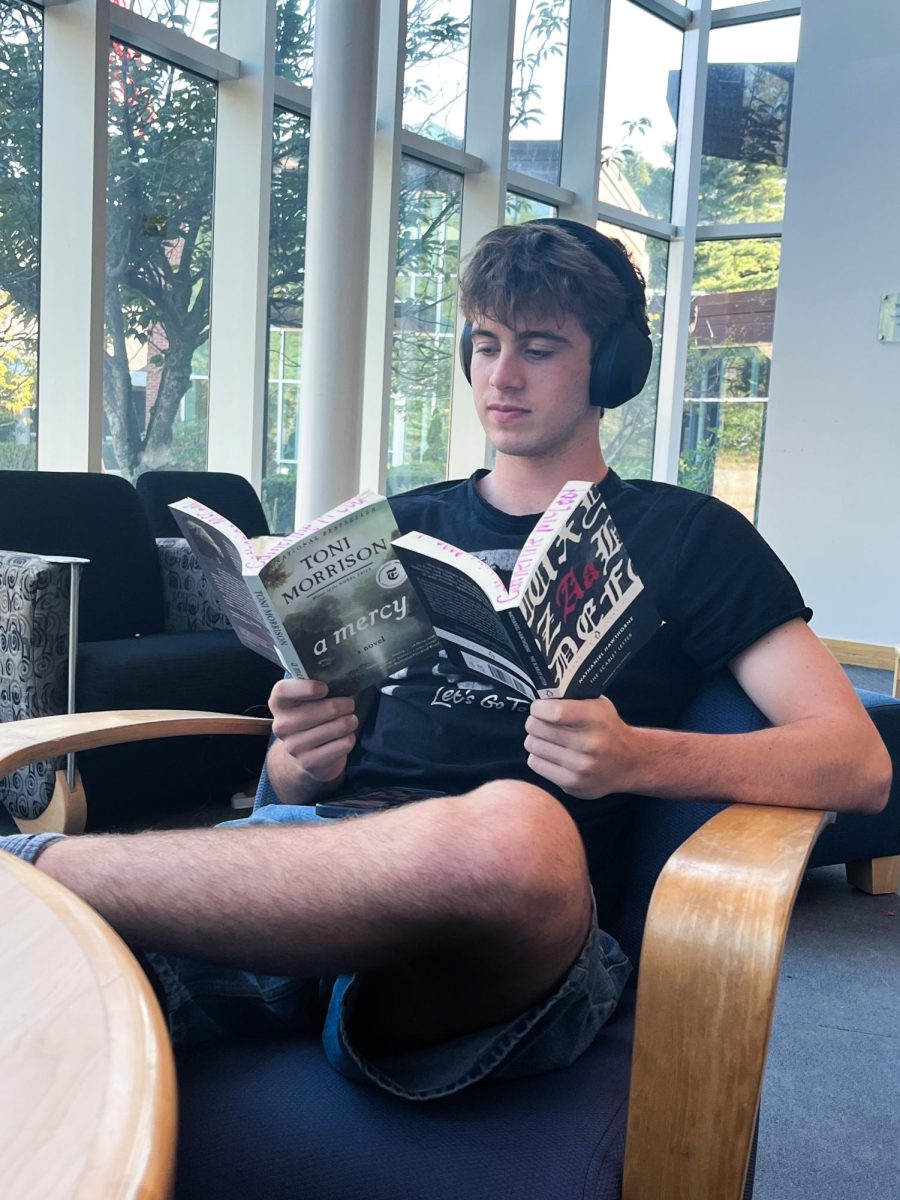

Part of what prevents Nobles students from speaking out in contentious conversations is a lack of confidence in their knowledge of a given topic. “There’s definitely give and take if you want to say something controversial because you need to be well-informed and stand by it,” Leah Farb (Class III) said. Speaking on a hot-button issue is putting oneself in a vulnerable position. For some students, to shy away from these issues is to avoid being drawn into an argument. “When I went to share, I second-guessed myself and didn’t just because I didn’t want to offend people with different beliefs,” Zach O’Connell (Class II) said.

Students’ identities play into what parts of their beliefs they feel comfortable sharing at school. Some students don’t feel like they can speak freely in the classroom. “I feel like in certain spaces, being a minority, there are certain things that you can and cannot say. If I’m with, for example, more minorities, I can say: ‘Oh, this makes me uncomfortable.’ But when you’re in a room full of white people, who probably don’t know what you’re going through, it’s a bit hard to say what you feel,” Kate Osakwe (Class IV) said.

It’s difficult for anyone to share an opinion that they think goes starkly against what those around them believe. When speaking out inside and outside of the classroom, students fear pushback from their peers. “In the social world at Nobles, you can get disciplined for any sort of political difference from the mainstream, left-wing perspective,” Levine said. This apprehension extends to teachers, as well. “It could be super tense, especially if a teacher that I really respected disagreed with something I fundamentally believe,” Farb said.

In the survey, 83.9% of students (±5.66%) reported that they think their teachers foster an environment where students can freely speak their minds. The way teachers approach both curriculum and also diving into current events outside of it can dictate whether students feel like their freedom of speech is protected. “I do think there are a lot of teachers at Nobles: Mr. Day, Mr. Baker, Mr. Bryant, and others who really encourage free thought in their classroom, despite the fact that everything they’re teaching is from a liberal perspective, with the exception of Mr. Baker,” Levine said.

According to the survey, 77.4% of students (±6.44%) said that individuals at Nobles discuss topics important to them as a community and in class. Over the course of the school year, various current events have been touched on in assembly. Most notably, a group of History Faculty gave background on the Israel-Palestine conflict in early October. Discussions of world and national news vary from class to class, however, and some students feel the issues most important to them—from the war in Ukraine to the crisis in Congo—are being ignored.

The ongoing Israel-Hamas war is an immensely pressing current event. Some students feel it should be talked about more at school. “I feel like we didn’t discuss the Israel-Palestine issue. Especially in history, it was kind of glossed over,” Olivia Golhar (Class II) said. Others echoed a similar sentiment. “I think we’ve addressed it, but we haven’t had many conversations about it,” Nabagereka said. Having these open conversations about the conflict is difficult. “I was definitely hesitant to speak out [in class],” Jonas Zatlyn-Weiner (Class II) said.

A host of issues are important to different members of the student population, yet opportunities for free debate and discussion are scarce. “I feel like a lot of the current political issues we don’t mention until it’s over or years later,” Golhar said. Students are concerned about sharing differing opinions, but some say that having these conversations will lead to a more well-informed and politically engaged student body. “I think that the first step to making it a less awkward environment for people who have unpopular beliefs is just to start sharing them and talking about them, just having more opportunities to do so,” Toby Gauld (Class II) said.

(Photo Credit: Zack Mittelstadt)