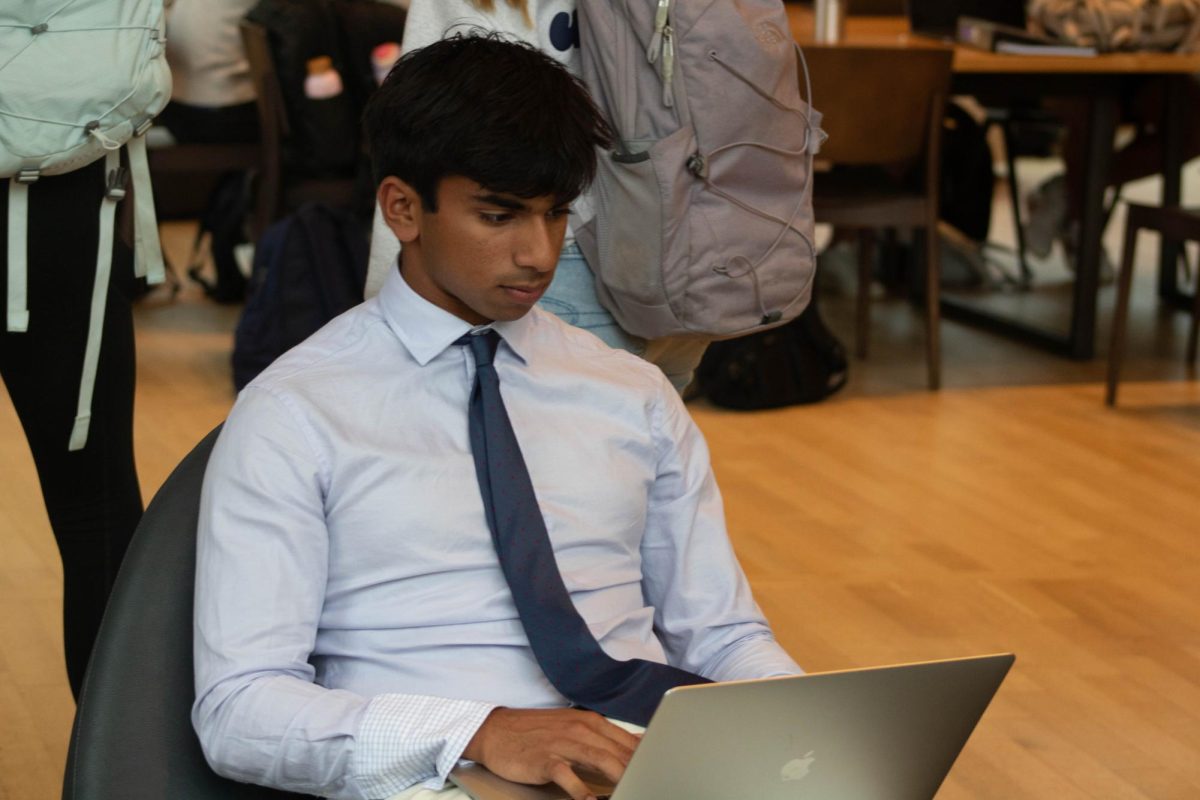

Take a stroll through the library and start counting how many people are playing Clash Royale. You’ll run out of fingers before you run out of players. The game, part card-flinging strategy, part digital bar fight, has clawed its way back into relevance. Trophies serve as the social currency: +30 for a win, -30 for a loss, and 15,000 buys you a reserved seat in the hall of fame.

The 2016 game has been called repetitive, pay-to-win, and flat-out toxic. By all means, Clash Royale should’ve been dead and buried alongside the likes of Flappy Bird and Angry Birds Space. Yet, here we are in 2025, hunched-over heads, thumbs flying, and the occasional damnation of a bloodline over Evo Mega Knight. Clash Royale has pulled off one of the greatest Lazarus acts in gaming. According to AppMagic, revenue is up 50% from last year, and Google searches have spiked 1000% in just six months.

Now, what could cause a resurrection like this, second only to Jesus Christ’s comeback tour? The reason: Jynxzi. A 24-year-old streamer who made his name in Rainbow Six Siege, he pivoted to Clash Royale last spring and dragged his audience with him. His chaotic streams and outrageous clip-farming, basically manufacturing viral moments for TikTok and YouTube, injected new life into the game. Suddenly, players who hadn’t touched the game since middle school were reinstalling to see if Hog Rider spam still works.

Supercell, Clash Royale’s developer, finally remembered it owned a cash cow worth feeding. For years, their updates were known to be unfair and catered to people with heavy wallets who weren’t afraid to spend a pretty penny to get the upper hand. Then the balance patches, those little updates that tweak cards so one doesn’t dominate the rest, got more fair, the grind less stale, and the $5 crying goblin emote hit the store. This grotesque little purchase, particularly, sold like hotcakes because its squeaky “mi-mi-mi” makes opponents want to snap their phones in half. For the first time in years, it felt like Supercell actually cared.

So that explains the what and how. The real question is why the fever at Nobles. The surprisingly simple answer: word of mouth.

“You get on, lose 1000 trophies, then hop off, then see a video and want to hop back on,” August Dix (Class III) said, who first played Clash three years ago but found himself redownloading just last April.

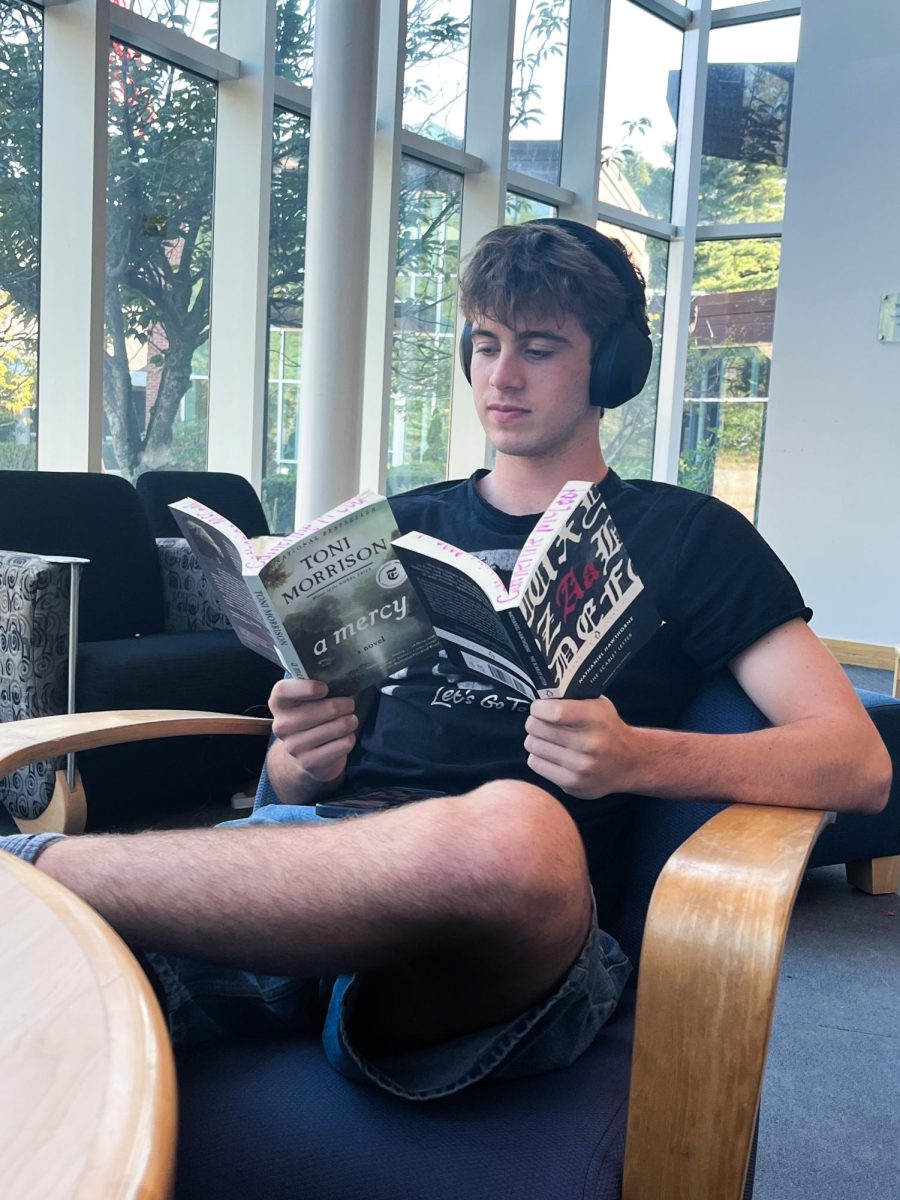

That cycle of rage-quitting and then crawling back is practically a rite of passage. Leo Meuse (Class I) remarked on how he found Clash a useful tool for making friends in middle school.

“It sounds really degenerate, but Clash helped me make friends, it did. It really did,” he said.

And then there’s Henry Hamilton (Class III), who sits at an eye-watering 15,700 trophies. His reason for playing is simple: friends.

“I got into the game because of the people around me,” he said.

But of course, not everyone is entirely convinced.

Nana Tabiri (Class I) said, “I’m definitely not opening Clash Royale because I like my mental health.”

Tabiri seems to know it all, as he’s been playing on and off for nearly eight years. He finds the game mind-numbing and irritating, but can’t stop coming back.

Call it hype if you want, Block Blast had its five minutes, but Clash feels different. It’s quick, competitive, and uniquely miserable. Where else can you lose to a Level 15 Boss Bandit three times in one night and still come limping back? The genius of Clash is its flexibility: grind every day and you climb the ladder; log in once a week to spam the pig shaking what he’s got emote and still feel like a part of the circus. Emotes, decks, and infamous cards (“X-bow players” might as well be a slur: basically the Clash version of the cousin who turns Monopoly into psychological warfare) carry tangible, social weight. It’s like fantasy football, distilled into three-minute bite-sized drama tantrums, trash talk, and heartbreak that you can sneak in on a bathroom break.

Why did Clash ultimately come back? The million-dollar question finally has an answer: it never really left. At Nobles, the clear draw is connection. Dix sees quitting and returning as unavoidable. Meuse credits the game with friendships. Hamilton plays because his friends do. Even Tabiri, who swears it’s bad for his brain, can’t quit. That tug-of-war is the whole point. Clash has become a low-stakes way to bond, compete, and occasionally lose your mind. Maybe that’s why it works: three guaranteed minutes of shared frustration and laughter. So, the next time you see someone slamming their phone down in the library, don’t assume it’s crappy Wi-Fi or homework overload. Chances are they just had their day ruined by an overleveled Pekka-Goblin Giant freakazoid.